July 3, 2009 – At “The End of the World” I met Maria. Beneath a tent of blankets on a steep bank, surrounded by discarded syringes and blood, she unfolded her foil and proceeded to smoke heroin.

proceeded to smoke heroin.

The district in which she lives near Lisbon gained its name and reputation from illegal drugs. But as I sat on a rock and watched her daily ritual, I was aware that Maria is part of an extraordinary and controversial experiment. In almost every other place in the world, what she is doing is crime. Here, though, she can be confident her drug use will not end in prison.

Exactly eight years ago today, on July 1st 2001, Portugal decreed that the purchase, possession and use of any previously-illegal substance would no longer be considered a criminal offence. So, instead of police arresting users, at The End of the World, health and social workers now dispense the paraphernalia of heroin use.

Paula Vale de Andrade told me how her “street teams” have been able dramatically to cut HIV infections and drug deaths since the new law.

“When drug use was a crime, people were afraid to engage with the teams. But since decriminalisation, they know the police won’t be involved and they come forward. It has been a great improvement.”

Many had predicted disaster – that plane loads of “drug tourists” would descend on Portugal knowing that they couldn’t end up in court. But what one politician called “the promise of sun, beaches and any drug you like” simply hasn’t materialised.

In fact, overall drug consumption appears stable or down – government statistics suggest a 10% fall.

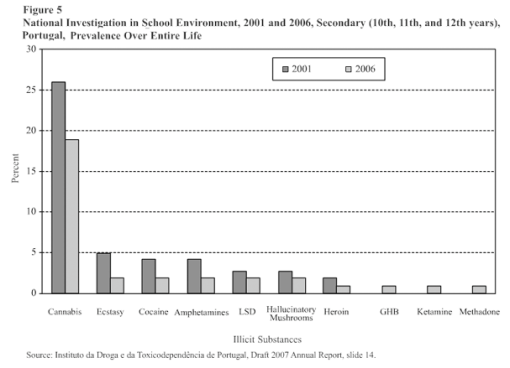

Among teenagers, the statistics suggest that the use of every illicit substance has fallen. The table below is from the Cato Institute’s white paper Drug Decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for Creating Fair and Successful Drug Policies.

I know there is some doubt over the methodology used in compiling some of these data, but what strikes me is that there is absolutely no evidence that drug use has risen.

Drug trafficking remains a serious criminal offence: Portugal hasn’t legalised drugs. But people caught with a quantity of drugs deemed for their personal use (roughly ten days’ supply) are sent to a local dissuasion commission panel.

The one I attended consisted of a social worker and a legal expert and they were looking at the case of Joanna, a heroin addict. The commission has the power to issue fines – while no longer a criminal offence, possession is still prohibited in Portugal – but the user here is addicted to drugs, so a fine is ruled inapplicable. The commission encourages her to go into treatment by offering to suspend other sanctions.

Some remain unconvinced that the new philosophy is working. The police officers I met on patrol in one of Lisbon’s more “notorious” districts question the statistics, particularly the suggestion that decriminalising drugs has caused drug use to fall. There is clearly frustration that people who were villains yesterday are victims today. But there’s also annoyance that in roughly a third of cases, drug users fail to attend the commission hearings when police send them there.

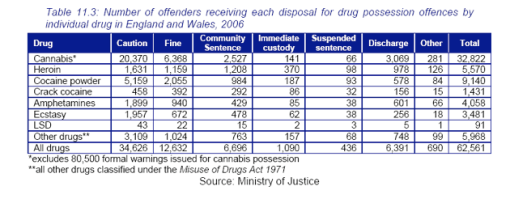

In the eight years since Portugal shocked the world with its drug policy, the idea that users need care not punishment has swept across Europe. In 10 EU countries, possession of some, if not all illegal substances is not generally pursued as a crime. In Britain, while officially the use of banned drugs is a criminal offence, Ministry of Justice figures (cited in UK Focal Point report [908Kb PDF]) show that 80% of people dealt with for possession are given a warning or a caution. Less than 1% – around 1,000 people a year – go to jail.

Portugal’s government is proud of its drugs policy. The prime minister stresses his personal role in its introduction, claiming the results are conclusive and the philosophy is popular.

Some question aspects of the system, but what Portugal’s controversial experiment has demonstrated is that, if you take the crime out of drug use, the sky doesn’t fall in. Source.

country’s rampant drug problem and focus instead on treating people for their addictions. He was roundly criticized for the idea, and America went on to prosecute a fruitless “war on drugs” that two decades later it is still clearly losing.

country’s rampant drug problem and focus instead on treating people for their addictions. He was roundly criticized for the idea, and America went on to prosecute a fruitless “war on drugs” that two decades later it is still clearly losing. Instead of throwing folks in jail, they began to focus on prevention and treatment. A new study has the early results, and they’re pretty inspiring. From Scientific American:

Instead of throwing folks in jail, they began to focus on prevention and treatment. A new study has the early results, and they’re pretty inspiring. From Scientific American: use of drugs, a day after he collapsed and died apparently from cardiac arrest at his rented Los Angeles home.

use of drugs, a day after he collapsed and died apparently from cardiac arrest at his rented Los Angeles home.