November 22, 2009 – With multiple initiatives in circulation and an Assembly bill gathering  headlines, discussions about legalizing marijuana have become part of California’s political discourse.

headlines, discussions about legalizing marijuana have become part of California’s political discourse.

Advocates on one side argue that the result will be an economic boon as tax revenues rolls in and jails rid themselves of nonviolent offenders. Defenders of prohibition say legalization would be a nightmare of stoned kids, addiction and highway deaths.

Or maybe the reality would be a lot more mundane.

“Most of the popular debate is dominated by two groups—avid pro-marijuana crowd, and the true prohibitionists,” said Michael Vitiello, a University of Pacific law professor who has written several articles on the topic, including a recent Wisconsin Law Review piece looking at the potential for legalization in California. Both sides, he said, are prone to “gross overstatements.”

By contrast, Vitiello calls himself a “tepid legalizer.” On the one hand, he said, he doesn’t “expect Western civilization as we know it to end” if pot becomes legal. He points to the widely-circulated statistic that per capita marijuana in the Netherlands, where pot has essentially been legal for years, is half that of the U.S — partially, he said, because few there view the drug as “cool.”

Medical research, Vitiello said, is increasingly pointing to the idea that people choose or avoid certain drugs based on their own brain chemistry. Marijuana is already so prevalent in California, he said, that most people who would use it probably already are.

On the other hand, he said he doubts projections that legalization will result in big tax revenues and thousands of non-violent offenders leaving prisons. The bigger impact would probably come on local jails, where many people head for a period after a marijuana arrest but never actually go to prison.

“The idea that we’re going to empty our prisons and save a billion, I don’t know how they’re getting that number,” Vitiello said.

Most in the debate agree that very few people are going to prison in California merely for smoking pot. The bigger issue is how many people are going back to prison on a parole violation of failing a drug test for marijuana. This has become a major rallying point for pro-legalization activists.

“My estimate is that there are thousands of people today in state prison in California for having done nothing but smoking marijuana because they were on parole,” said James Gray, a retired Orange County Superior Court judge who has become a major legalization and libertarian activists.

According to Corrections spokesman Paul Verke, only 256 were found to have violated parole in California last year solely for failing a marijuana test. He added that he did not know how many of these were returned to custody. Some in the legalization community say they have been seeking these figures, unsuccessfully, for years. “CCR will say it’s not many, parole officers will say they never do that, but on the other had we know family members who say that they have,” said Margaret Dooley- Sammuli, deputy state director with the Drug Policy Alliance. “Clearly this is an area where we don’t know what happening, and clearly this is a problem.”

Another area where the actual effect would be unclear is on tax revenue. The legalization initiative filed by the founder’s of Oakland’s Oaksterdam University, which teaches students about cultivation and other aspects of the medical marijuana business, cites a figure of $15 billion in illegal marijuana sales in California annually. While estimates vary, few contest that pot is California’s top cash crop, easily outpacing our state’s vaunted wine industry.

That initiative calls for unspecified taxes. AB 390, the marijuana legalization bill being carried by Assemblyman Tom Ammiano, D-San Francisco, calls for a tax of $50 an ounce. Growers would pay a licensing fee of $5,000, with a $2,500 annual renewal. While it’s very unlikely AB 390 will get anywhere, some have pointed to these fees as a possible model of taxation.

But the state would be trying to overlay these taxes on an already-thriving illegal market, with numerous large operations already running without the knowledge of authorities. Legalization would also likely inspire more people to grow their own. Few people are going to grow and ferment their own wine, or grow and roll their own tobacco for that matter. But small amounts of marijuana can be successfully grown by anyone who can keep a houseplant alive.

In fact, Vitiello said, there is a natural tension between the desire to relax law enforcement and the hope of brining in tax revenue. If not reporting a crop is nothing more than a minor tax offense, he said, there will be little incentive for most people to report to the Franchise Tax Board. Making penalties strong enough to get people to report, however, could actually send more people to prison, at least in the short term.

John Lovell, lobbyist for the California Peace Officers Association and several other law enforcement groups, scoffs at the idea that legal pot would be a moneymaker for the state.

“The hard dollars will be far more than any revenue that is brought in through any kind of spurious tax effort,” Lovell said.

Lovell referred to studies from Maryland and British Columbia that he said point to the dangers of people driving while under the influence of marijuana—a problem he said would get much worse under legalization. He also pointed to a RAND Corp. study he said that shows pot taxes would be a fraction of what proponents claim. Most of the tax penalties in current bills and initiatives, he said, amount to little more than “licensing fees.”

Another issue is the penalties for selling to minors. Many proponents have said the penalties should be similar to those for adults who procure alcohol for kids. Both the Ammiano bill and Oaksterdam initiative allow legislative leeway in determining what these penalties should be.

“These things are negotiable,” Ammiano said. “My druthers are that we do look at sentencing and determinate sentencing. There are obviously areas we can negotiate on.”

Then there’s the question of where people could buy it. Most models point to a highly-regulated distribution system, perhaps akin to the state-run liquor stores in Washington State.

There could also be major local differences. There’s already been a decade of testing on what this might look like, in the form of the medical marijuana dispensaries that have been operating since California voters passed Proposition 215 by a wide margin in 1996. Some areas, particularly Los Angeles, have reported significant problems, with a large number of dispensaries operating. The more likely model might be West Hollywood, which operates a small number of heavily-regulated but thriving operations.

“What it’s going to look like in the future will entirely depend on the locals,” said Dale Clare, executive chancellor of Oaksterdam.

Clare also said that they’re set to pass half a million signatures on their initiative by next week. Oaksterdam founder Richard Lee has been quoted saying they will be able to marshal $20 million in donations to the initiative once it lands on next year’s ballot—a figure likely to be countered by millions from group’s opposing the measure.

Clare also points to an April Field Poll that found that 56 percent of voters would approve a legalization measure. This conflicts with a Capitol Weekly/Probolsky Research poll earlier this month that found likely voters opposed such a measure, 52 percent to 38 percent.

But the trend lines are clearly headed towards legalization. A February article on the popular political blog FiveThirtyEight.com said that support for marijuana legalization nationwide had passed the 40 percent threshold. Given greater support among younger voters and greatest opposition from older ones, “legalization would achieve 60 percent support at some point in 2022 or 2023,” according to author Nate Silver.

“If it goes to the ballot and fails, we’re that much closer for 2012,” Clare said. “This is an education campaign.”

as a “currency” to bring harder drugs into the country.

as a “currency” to bring harder drugs into the country.

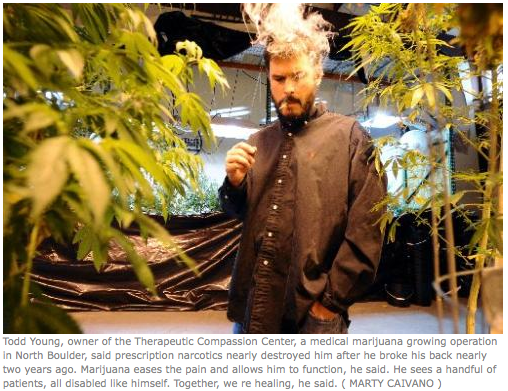

Todd Young is concerned.

Todd Young is concerned. from her doctor after suffering more than a decade of debilitating, undiagnosed pain, she had no idea where to go to get her medicine.

from her doctor after suffering more than a decade of debilitating, undiagnosed pain, she had no idea where to go to get her medicine. “We cannot have a Wild West-type situation where we have dispensaries on every corner like convenience stores,” said state Sen. Chris Romer, D-Denver, who plans to introduce legislation next year that would eliminate retail-style dispensaries and place extra scrutiny on patients under 25.

“We cannot have a Wild West-type situation where we have dispensaries on every corner like convenience stores,” said state Sen. Chris Romer, D-Denver, who plans to introduce legislation next year that would eliminate retail-style dispensaries and place extra scrutiny on patients under 25. Cannabis Therapy Institute, an advocacy group. “All that’s new is it’s coming out of the black market. This is what the legalization of a previously criminal enterprise looks like.”

Cannabis Therapy Institute, an advocacy group. “All that’s new is it’s coming out of the black market. This is what the legalization of a previously criminal enterprise looks like.”